The Big Migrations

A one stop shop that shows how migration changed our world

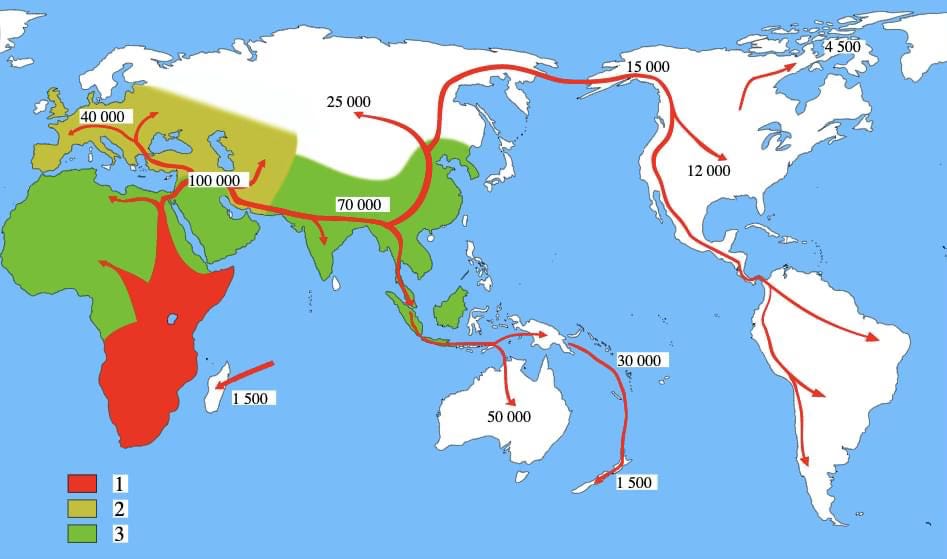

Human beings have always moved. When I say human beings, I should really start by talking about how Homo sapiens, our species, moved from regions across Africa into what we now call the Arabian Peninsula. Some research tells us that small groups of Homo sapiens left Africa during a period of time when the Sahara was lush and green, eventually settling in places in the Levant. Ancient bones in the Skhul and Qafzeh caves In Israel are fossils of Homo sapiens dated to about 120,000–90,000 years ago, making them among the earliest known remains of modern humans outside Africa.

Movement made us.

Humans moved into Eurasia around 60,000–40,000 years ago. Modern humans reached the Middle East, Central Asia, Europe, South Asia, and eventually Australia. Early humans interbred with Neanderthal and Denisovan groups in Eurasia. Then we had the peopling of the Americas (20,000–15,000 years ago) via the Bering land bridge from Siberia to Alaska. Humans travelled even further, eventually settling in the Pacific regions 10,000–3,000 years ago.

But the history of migration doesn't stop there. Migration continued and shaped our society - everything from food, music, religion, clothing, weaponry to language and custom.

The Farming Migrations came next, between 10,000 and 4000 BCE. In essence, farming that flourished in the Fertile Crescent spread into Europe, North Africa and South Asia. We also saw migration from Anatolia (Turkey) taking farming into the Balkans and across Europe, where our ancestors mixed with hunter-gatherer groups.

We then saw early urban societies forming, perhaps not in the sense we understand now, but in Mesopotamia, in Egypt, in the Indus Valley and Chinese neolithic cultures.

Between 4000-1000 BCE, one of the most crucial migrations happens and it brings with it our languages. Also known as the Bronze Age, some theories suggest that there were significant migrations from Pontic-Caspian steppe (although it is also suggested that this migration started in Anatolia). This movement of semi-nomadic herders saw the domestication of the horse and the development and use of the wheel. They moved west into Europe and south into the Middle East, as well as East into Central Asia, bringing with them the Indo-European language family, spoken by half of the world today. This language development gave us English, Spanish, Persian, Hindi and so on. It gave us bronze weaponry. In storytelling, it gave us shared mythologies and religious ideas too. It brought forth Vedic culture in South Asia.

Movement of humans featured heavily in Greek and Roman colonisation. Some might argue that Greek colonisation was a result of trade, overpopulation and exploration, where Greek city states formed colonies in Asia Minor, North Africa and near the Black Sea. Roman expansion saw movement into Britain, France, Spain and more (and I simplify here) possibly more for conquest and empire building. We know what both cultures brought to the world in art, in literature, in politics and so on. It brought cultural blending, with Roman gods merging with local deities, creating new cultures and religious observation. The Ivory Bangle Lady of York dates from these migrations, with her North African heritage. The remains of Black soldiers have been found near Hadrian’s Wall, where they were working and where they had settled.

Viking migrations and exploration took place between the 8th and 11th centuries. We are familiar with the migration of Vikings to Britain, and we are aware of the impact of their language and culture on Britain today. We take every day words, such as sky, husband, window, from Old Norse. Our pronouns - they/their/them - also Old Norse. Our towns, even the one I live in, bear the mark of Viking language. The -by in Derby tells me how movement and migration shaped my city.

It is fascinating to see, too, how far the Vikings travelled and where they traded. Tens of thousands of silver coins minted in the Abbasid Caliphate (Iraq, Iran) and other Islamic centres have been found in Sweden, Russia, and the Baltic. Islamic silks have been found in Viking graves and huge coin hoards in Gotland contain more Arabic silver than could be believed!

The Mongol migrations weren’t just about conquest — they created an interconnected Afro-Eurasian world, with trade and cultural exchange flowing across the largest empire ever seen. From the early 13th century, Genghis Khan united the Mongolian nomadic steppe tribes to create the largest contiguous land empire in history. What came with this was incredibly important. The Silk Roads heralded a golden age of trade, taking with them ideas about technology, and contributing to what some have called a ‘cross-pollination’ of arts, science and medicine. By linking East Asian to West Asia and Europe, the Mongols instigated the flourishing of postal systems and relay stations. People moved and ideas moved with them. It wasn’t all roses, naturally. Disease and warfare were also common at this scale.

Forced movement also created large migrations. Jewish people have a long history of forced movement, dating back to Babylonian exile in the 6th century BCE. In the Early Modern period, Jewish populations at times flourished under some rulers and were expelled by others, as exemplified by changes in Spanish rule. Pogroms also led to the wide-ranging Jewish diaspora. Jewish culture and philosophy flourished in some spaces, bringing us Maimonides and Spinoza.

As we move into the 16th century, we are faced with yet more forced movement in the Atlantic Slave Trade. The forced migration of millions of Africans to the Americas was instrumental in forming the modern United States and the Caribbean. With them, Africans brought their languages, their religions, their music and their food. In this, a bloody moment, forced migration shaped the western world and continues to shape it today. The narrative around migration and colour was now steeped in racism, not a new phenomenon. It rested in an us vs them mentality.

In the history of migration, the us vs them narrative was compounded by European colonisation that saw movement across the world, instigated by European superpowers. Not only did we have ‘settlers’ (also known as colonisers), administrators and soldiers, we had indentured labour, such as those from Indian and Chinese backgrounds who moved under contract to the colonies in the Caribbean, Africa and Southeast Asia. The ayahs and the lascars travelled oceans in service of British families, only to be abandoned. The Portuguese in India, the Germans in East Africa, the French in North Africa, the Spanish in the Americas - created strife and subjugation, but also led to movement of colonised people to their colonising countries. The conflict and famine that came about due to colonial decision making led to mass migration in conflict zones in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as the Irish migration in the 1840s to the United States. Irish culture is now embedded in US consciousness.

As we approach modern and contemporary migrations, we can see that movement is still happening, but the rhetoric around it is soaked in ‘othering’, as perhaps it has been for a long while. Migrations post World War Two saw refugees scatter across Europe. Rebuilding and reconstructing saw the call for colonial workers to move.

The Empire Windrush migration is one of the greatest migrations to occur in a UK context. The arrival of Caribbean workers to support the rejuvenation of Britain brought a revolution in food, in music, in art and in innovation. Our society is profoundly impacted positively by those migrants. The 20th century also saw the expulsion of Asians from East Africa in 1972.

That brought my family from former colonies to England. It brought me, in a roundabout way.

Migration won’t stop there. With the impact of climate change, with the prevalence of international conflict, we already see movements of people at large scale from war-torn, famine-ridden places. They, like many migrants before them, are seeking safety, seeking security. Many of their places of origin are still recovering from British intervention in their statehood and development. From Syria, Sudan and Afghanistan, they move to places that will have them, knowing full well that they will be seen as a threat.

And yet, the history of migration tells us that with each movement of people, we have developed as a species. Our lives have changed immeasurably and positively. The very aspects of our lives that we take for granted - language, music, food, religion, art, theatre, work, education - all are indelibly imprinted with the legacy of migrants.